https://www.facebook.com/johnnycash/?checkpoint_src=anyhttps://www.johnnycash.com/

GuitarClub.ca Johnny Cash Guitar Tabs https://guitarclub.ca/tab-realm/?tabmode=artist&tabvalue=Johnny+Cash

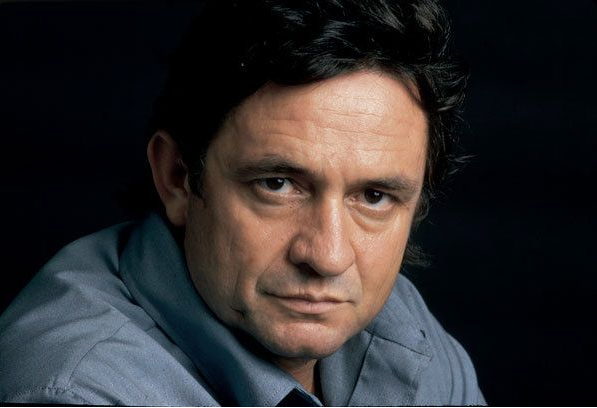

John R. Cash (born J. R. Cash; February 26, 1932 – September 12, 2003) was an American singer-songwriter. Most of Cash’s music contains themes of sorrow, moral tribulation, and redemption, especially songs from the later stages of his career.[3][4] He was known for his deep, calm, bass-baritone voice,[a][5] the distinctive sound of his backing band, the Tennessee Three, that was characterized by its train-like chugging guitar rhythms, a rebelliousness[6][7] coupled with an increasingly somber and humble demeanor,[3] and his free prison concerts.[8] Cash wore a trademark all-black stage wardrobe, which earned him the nickname “Man in Black”.[b]

Born to poor cotton farmers in Kingsland, Arkansas, Cash grew up on gospel music and played on a local radio station in high school. He served four years in the Air Force, much of it in West Germany. After his return to the United States, he rose to fame during the mid-1950s in the burgeoning rockabilly scene in Memphis, Tennessee. He traditionally began his concerts by introducing himself with “Hello, I’m Johnny Cash”.[c] He began to follow that by “Folsom Prison Blues”, one of his signature songs. His other signature songs include “I Walk the Line”, “Ring of Fire”, “Get Rhythm”, and “Man in Black”. He also recorded humorous numbers like “One Piece at a Time” and “A Boy Named Sue”, a duet with his future wife June called “Jackson” (followed by many further duets after they married), and railroad songs such as “Hey, Porter”, “Orange Blossom Special”, and “Rock Island Line”.[11] During the last stage of his career, he covered songs by contemporary rock artists; among his most notable covers were “Hurt” by Nine Inch Nails, “Rusty Cage” by Soundgarden, and “Personal Jesus” by Depeche Mode.

Cash is one of the best-selling music artists of all time, having sold more than 90 million records worldwide.[12][13] His genre-spanning music embraced country, rock and roll, rockabilly, blues, folk, and gospel sounds. This crossover appeal earned him the rare honor of being inducted into the Country Music, Rock and Roll, and Gospel Music Halls of Fame.

Early life

Cash’s boyhood home in Dyess, Arkansas, where he lived from the age of three in 1935 until he finished high school in 1950. The property, pictured here in 2021, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The home was renovated in 2011 to look as it did when Cash lived there as a child.

Cash was born J. R. Cash in Kingsland, Arkansas, on February 26, 1932,[14][15] to Carrie Cloveree (née Rivers) and Ray Cash. He had three older siblings, Roy, Margaret Louise, and Jack, and three younger siblings, Reba, Joanne, and Tommy (who also became a successful country artist).[16][17] He was primarily of English and Scottish descent.[18][19][20]

His paternal grandmother claimed Cherokee ancestry. But a DNA test of Cash’s daughter Rosanne in 2021 on Finding Your Roots, hosted by historian Henry Louis Gates Jr, found she has no known Native American markers.[21] The researchers did find DNA for African ancestry on both sides of her family. They were able to document her maternal ancestry by historic records, dating to her great-great-great-great-grandmother Sarah Shields, a mixed-race woman born into slavery and freed by her white father in 1848, along with her eight siblings. Her paternal DNA suggested African ancestry in a similar time frame among Johnny Cash’s family.[21]

After meeting with the then-laird of Falkland in Fife, Major Michael Crichton-Stuart, Cash became interested in his Scots ancestry. He traced his Scottish surname to 11th-century Fife. [22][23][24] Cash Loch and other locations in Fife bear the surname of his father.[22] He is a distant cousin of British Conservative politician Sir William Cash.[25] He also had English ancestry.

Because his mother wanted to name him John and his father preferred to name him Ray when he was born, they compromised on the initials “J. R.”[26] But when Cash enlisted in the Air Force after high school, he was not permitted to use initials as a first name. He adopted the name “John R. Cash”. In 1955, when signing with Sun Records, he started using the name “Johnny Cash”.[7]

In March 1935, when Cash was three years old, the family settled in Dyess, Arkansas, a New Deal colony established during the Great Depression under the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. It was intended to give poor families the opportunity to work land that they might later own.[27]

From the age of five, Cash worked in cotton fields with his family, singing with them as they worked. Dyess and the Cash farm suffered a flood during his childhood. Later he wrote the song “Five Feet High and Rising”.[28] His family’s economic and personal struggles during the Great Depression gave him a lifelong sympathy for the poor and working class, and inspired many of his songs.

In 1944,[29] Cash’s older brother Jack, with whom he was close, was cut almost in two by an unguarded table saw at work. He died of his wounds a week later.[30] According to Cash’s autobiography, he, his mother, and Jack all had a sense of foreboding about that day; his mother urged Jack to skip work and go fishing with Cash, but Jack insisted on working as the family needed the money. Cash often spoke of the guilt he felt over the incident. He would say that he looked forward to “meeting [his] brother in Heaven”.[7]

Cash’s early memories were dominated by gospel music and radio. Taught guitar by his mother and a childhood friend, Cash began playing and writing songs at the age of 12. When young, Cash had a high-tenor voice, before becoming a bass-baritone after his voice changed.[31]

In high school, he sang on a local Arkansas radio station. Decades later, he released an album of traditional gospel songs called My Mother’s Hymn Book. He was also strongly influenced by traditional Irish music, which he heard performed weekly by Dennis Day on the Jack Benny radio program.[32]

Cash enlisted in the Air Force on July 7, 1950, shortly after the start of the Korean War.[33] After basic training at Lackland Air Force Base and technical training at Brooks Air Force Base, both in San Antonio, Texas, Cash was assigned to the 12th Radio Squadron Mobile of the U.S. Air Force Security Service at Landsberg, West Germany. While in San Antonio, he met Vivian Liberto, an attractive girl of Sicilian, Irish and German ancestry. They dated briefly before his departure. During the years he served overseas, they exchanged thousands of letters.

He worked in West Germany as a Morse code operator, intercepting Soviet Army transmissions. While working this job, Cash was said to be the first American to be given the news of Joseph Stalin’s death (supplied via Morse code). His daughter, Rosanne, said that Cash had recounted the story many times over the years.[34][35][36] While at Landsberg, he created his first band, “The Landsberg Barbarians”.[37] On July 3, 1954, he was honorably discharged as a staff sergeant, and he returned to Texas.[38] During his military service, he acquired a distinctive scar on the right side of his jaw as a result of surgery to remove a cyst.[39][40]

Soon after his return, Cash married Vivian Liberto in San Antonio. She had grown up Catholic and was married in the church by her paternal uncle, Father Franco Liberto

Career

Early career

Publicity photo for Sun Records, 1955

In 1954, Cash and his first wife Vivian moved to Memphis, Tennessee. He sold appliances while studying to be a radio announcer. At night, he played with guitarist Luther Perkins and bassist Marshall Grant. Perkins and Grant were known as the Tennessee Two. Cash worked up the courage to visit the Sun Records studio, hoping to get a recording contract.[41] He auditioned for Sam Phillips by singing mostly gospel songs, only to learn from the producer that he no longer recorded gospel music. Phillips was rumored to have told Cash to “go home and sin, then come back with a song I can sell”. In a 2002 interview, Cash denied that Phillips made any such comment.[42] Cash eventually won over the producer with new songs delivered in his early rockabilly style. In 1955, Cash made his first recordings at Sun, “Hey Porter” and “Cry! Cry! Cry!”, which were released in late June and met with success on the country hit parade.

On December 4, 1956, Elvis Presley dropped in on Phillips while Carl Perkins was in the studio cutting new tracks, with Jerry Lee Lewis backing him on piano. Cash was also in the studio, and the four started an impromptu jam session. Phillips left the tapes running and the recordings, almost half of which were gospel songs, survived. They have since been released under the title Million Dollar Quartet. In Cash: the Autobiography, Cash wrote that he was the farthest from the microphone and sang in a higher pitch to blend in with Elvis.

Cash’s next record, “Folsom Prison Blues”, made the country top five. His “I Walk the Line” became number one on the country charts and entered the pop charts top 20. “Home of the Blues” followed, recorded in July 1957. That same year, Cash became the first Sun artist to release a long-playing album. Although he was Sun’s most consistently selling and prolific artist at that time, Cash felt constrained by his contract with the small label. Phillips did not want Cash to record gospel and was paying him a 3% royalty rather than the standard rate of 5%. Presley had already left Sun, and Cash felt that Phillips was focusing most of his attention and promotion on Lewis.

In 1958, Cash left Phillips to sign a lucrative offer with Columbia Records. His single “Don’t Take Your Guns to Town” became one of his biggest hits. He recorded a collection of gospel songs for his second album for Columbia. However, Cash left behind such a backlog of recordings with Sun that Phillips continued to release new singles and albums featuring previously unreleased material until as late as 1964. Cash was in the unusual position of having new releases out on two labels concurrently. Sun’s 1960 release, a cover of “Oh Lonesome Me”, made it to number 13 on the C&W charts.[d]

Cash on the cover of Cash Box magazine, September 7, 1957

Early in his career, Cash was given the teasing nickname “the Undertaker” by fellow artists because of his habit of wearing black clothes. He said he chose them because they were easier to keep looking clean on long tours.[43]

In the early 1960s, Cash toured with the Carter Family, which by this time regularly included Mother Maybelle’s daughters, Anita, June, and Helen. June later recalled admiring him from afar during these tours. In the 1960s, he appeared on Pete Seeger’s short-lived television series Rainbow Quest.[44] He also acted in, and wrote and sang the opening theme for, a 1961 film entitled Five Minutes to Live. It was later re-released as Door-to-door Maniac.

Cash’s career was handled by Saul Holiff, a London, Ontario, promoter. Their relationship was the subject of Saul’s son’s biopic My Father and the Man in Black.[45]

Outlaw image

As his career was taking off in the late 1950s, Cash started drinking heavily and became addicted to amphetamines and barbiturates. For a brief time, he shared an apartment in Nashville with Waylon Jennings, who was deeply addicted to amphetamines. Cash would use the stimulants to stay awake during tours. Friends joked about his “nervousness” and erratic behavior, many ignoring the warning signs of his worsening drug addiction.

Although he was in many ways spiraling out of control, Cash could still deliver hits due to his frenetic creativity. His rendition of “Ring of Fire” was a crossover hit, reaching number one on the country charts and entering the top 20 on the pop charts. It was originally performed by June Carter’s sister, but the signature mariachi-style horn arrangement was provided by Cash.[46] He said that it had come to him in a dream.

His first wife Vivian (Liberto) Cash claimed a different version of the origins of “Ring of Fire”. In her book, I Walked the Line: My Life with Johnny (2007), Liberto says that Cash gave Carter half the songwriting credit for monetary reasons.[47]

In June 1965, Cash’s camper caught fire during a fishing trip with his nephew Damon Fielder in Los Padres National Forest in California. It set off a forest fire that burned several hundred acres and nearly caused his death.[48][49] Cash claimed that the fire was caused by sparks from a defective exhaust system on his camper, but Fielder thought that Cash started a fire to stay warm and, under the influence of drugs, failed to notice the fire getting out of control.[50] When the judge asked Cash why he did it, Cash said, “I didn’t do it, my truck did, and it’s dead, so you can’t question it.”[51]

The fire destroyed 508 acres (206 ha), burned the foliage off three mountains and drove off 49 of the refuge’s 53 endangered California condors.[52] Cash was unrepentant and said, “I don’t care about your damn yellow buzzards.”[53] The federal government sued him and was awarded $125,172. Cash eventually settled the case and paid $82,001.[54]

The Tennessee Three with Cash in 1963

Although Cash cultivated a romantic outlaw image, he never served a prison sentence. Despite landing in jail seven times for misdemeanors, he was held only one night each time. On May 11, 1965, he was arrested in Starkville, Mississippi, for trespassing late at night onto private property to pick flowers. (He used this incident as the basis for the song “Starkville City Jail”. He discussed this on his live At San Quentin album.)[55]

While on tour later that year, he was arrested October 4 in El Paso, Texas, by a narcotics squad. The officers suspected he was smuggling heroin from Mexico, but found instead 688 Dexedrine capsules (amphetamines) and 475 Equanil (sedatives or tranquilizers) tablets hidden inside his guitar case. Because the pills were prescription drugs rather than illegal narcotics, Cash received a suspended sentence. He posted a $1,500 bond and was released until his arraignment.[56]

In this period of the mid-1960s, Cash released a number of concept albums. His Bitter Tears (1964) was devoted to spoken word and songs addressing the plight of Native Americans and mistreatment by the government. While initially reaching charts, this album met with resistance from some fans and radio stations, which rejected its controversial take on social issues.

In 2011, a book was published about it, leading to a re-recording of the songs by contemporary artists and the making of a documentary film about Cash’s efforts with the album. This film was aired on PBS in February and November 2016. His Sings the Ballads of the True West (1965) was an experimental double record, mixing authentic frontier songs with Cash’s spoken narration.

Reaching a low with his severe drug addiction and destructive behavior, Cash and his first wife divorced after having separated in 1962. Some venues cancelled his performances, but he continued to find success. In 1967, Cash’s duet with June Carter, “Jackson”, won a Grammy Award.[57]

Cash was last arrested in 1967 in Walker County, Georgia, after police found he was carrying a bag of prescription pills when in a car accident. Cash attempted to bribe a local deputy, who turned the money down. He was jailed for the night in LaFayette, Georgia. Sheriff Ralph Jones released him after giving him a long talk, warning him about the danger of his behavior and wasted potential. Cash credited that experience with helping him turn around and save his life. He later returned to LaFayette to play a benefit concert; it attracted 12,000 people (the city population was less than 9,000 at the time) and raised $75,000 for the high school.[58]

Reflecting on his past in a 1997 interview, Cash noted: “I was taking the pills for awhile, and then the pills started taking me.”[59] June, Maybelle, and Ezra Carter moved into Cash’s mansion for a month to help him get off drugs. Cash proposed onstage to June on February 22, 1968, at a concert at the London Gardens in London, Ontario, Canada. The couple married a week later (on March 1) in Franklin, Kentucky. She had agreed to marry Cash after he had “cleaned up.”[60]

Cash’s journey included rediscovery of his Christian faith. He took an “altar call” in Evangel Temple, a small church in the Nashville area, pastored by Reverend Jimmie Rodgers Snow, son of country music legend Hank Snow. According to Marshall Grant, though, Cash did not completely stop using amphetamines in 1968; and did not fully end drug use for another two years. He was drug-free for a period of seven years. In his memoir about time with Cash, Grant said that the birth of Cash’s son, John Carter Cash, inspired the singer to end his dependence.[61]

Cash began using amphetamines again in 1977. By 1983, he was deeply addicted again. He entered rehab at the Betty Ford Clinic in Rancho Mirage for treatment. He stayed off drugs for several years, but relapsed.

In 1989, he entered Nashville’s Cumberland Heights Alcohol and Drug Treatment Center. In 1992, he started care at the Loma Linda Behavioral Medicine Center in Loma Linda, California, for his final rehabilitation treatment. (Several months later, his son followed him into this facility for treatment.)[62][63]

Discography

Main articles: Johnny Cash albums discography, Johnny Cash singles discography, and Johnny Cash Sun Records discography

See also: List of songs recorded by Johnny Cash

Johnny Cash with His Hot and Blue Guitar! (1957)

The Fabulous Johnny Cash (1958)

Hymns by Johnny Cash (1959)

Songs of Our Soil (1959)

Now, There Was a Song! (1960)

Ride This Train (1960)

Hymns from the Heart (1962)

The Sound of Johnny Cash (1962)

Blood, Sweat and Tears (1963)

The Christmas Spirit (1963)

Keep on the Sunny Side (with the Carter Family) (1964)

I Walk the Line (1964)

Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian (1964)

Orange Blossom Special (1965)

Johnny Cash Sings the Ballads of the True West (1965)

Everybody Loves a Nut (1966)

Happiness Is You (1966)

Carryin’ On with Johnny Cash & June Carter (with June Carter) (1967)

From Sea to Shining Sea (1968)

The Holy Land (1969)

Hello, I’m Johnny Cash (1970)

Man in Black (1971)

A Thing Called Love (1972)

America: A 200-Year Salute in Story and Song (1972)

The Johnny Cash Family Christmas (1972)

Any Old Wind That Blows (1973)

Johnny Cash and His Woman (with June Carter Cash) (1973)

Ragged Old Flag (1974)

The Junkie and the Juicehead Minus Me (1974)

The Johnny Cash Children’s Album (1975)

Johnny Cash Sings Precious Memories (1975)

John R. Cash (1975)

Look at Them Beans (1975)

One Piece at a Time (1976)

The Last Gunfighter Ballad (1977)

The Rambler (1977)

I Would Like to See You Again (1978)

Gone Girl (1978)

Silver (1979)

A Believer Sings the Truth (1979)

Johnny Cash Sings with the BC Goodpasture Christian School (1979)

Rockabilly Blues (1980)

Classic Christmas (1980)

The Baron (1981)

The Adventures of Johnny Cash (1982)

Johnny 99 (1983)

Highwayman (with Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson & Kris Kristofferson) (1985)

Rainbow (1985)

Heroes (with Waylon Jennings) (1986)

Class of ’55 (with Roy Orbison, Jerry Lee Lewis & Carl Perkins) (1986)

Believe in Him (1986)

Johnny Cash Is Coming to Town (1987)

Classic Cash: Hall of Fame Series (1988)

Water from the Wells of Home (1988)

Boom Chicka Boom (1990)

Highwayman 2 (with Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson & Kris Kristofferson) (1990)

The Mystery of Life (1991)

Country Christmas (1991)

American Recordings (1994)

The Road Goes on Forever (with Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson & Kris Kristofferson) (1995)

American II: Unchained (1996)

American III: Solitary Man (2000)

American IV: The Man Comes Around (2002)

My Mother’s Hymn Book (2004)

American V: A Hundred Highways (2006)

American VI: Ain’t No Grave (2010)

Out Among the Stars (2014)

Songwriter (2024)

Filmography

Film

Year Title Role Notes

1961 Five Minutes to Live Johnny Cabot Also titled Door-To-Door Maniac

1967 The Road to Nashville Himself

1971 A Gunfight Abe Cross

1973 Gospel Road: A Story of Jesus Narrator/Himself

1983 Kairei Uncle John Japanese film[181]

1994 Gene Autry, Melody of the West Narrator Documentary film; voice acting role

2003 The Hunted Narrator Voice acting role

2014 The Winding Stream Interview subject Documentary film; archive footage

Television

Year Title Role Notes

1959 Shotgun Slade Sheriff Episode: “The Stalkers”

1959 Wagon Train Frank Hoag Episode: “The C.L. Harding Story

1960 The Rebel Pratt Episode: “The Death of Gray”

1961 The Deputy Bo Braddock Episode: “The Deathly Quiet”

1969–1971 The Johnny Cash Show Himself – host and performer 58 episodes

1970 NET Playhouse John Ross Episode: “Trail of Tears”

1970 The Partridge Family Variety Show Host Episode: “What? Get Out of Show Business?”

1973–1992 Sesame Street Himself 4 episodes

1974–1988 Hee Haw Himself 4 episodes

1974 Columbo Tommy Brown Episode: “Swan Song”

1974 Johnny Cash Ridin’ the Rails—The Great American Train Story Himself

1976 Johnny Cash and Friends Himself 4 episodes

1976 Little House on the Prairie Caleb Hodgekiss Episode: “The Collection”

1976–1985 Johnny Cash specials (various titles) Himself 15 specials

1978 Thaddeus Rose and Eddie Thaddeus Rose Television film

1978 Steve Martin: A Wild and Crazy Guy Himself Television special[182]

1980 The Muppet Show Himself Episode: “#5.21”

1981 The Pride of Jesse Hallam Jesse Hallam Television film

1982 Saturday Night Live Himself Episode: “Johnny Cash/Elton John”

1983 Murder in Coweta County Lamarr Potts Television film; also producer

1984 The Baron and the Kid The Baron

Will Television film

1985 North and South John Brown 6 episodes

1986 The Last Days of Frank and Jesse James Frank James Television film

1986 Stagecoach Curly Wilcox Television film

1988 The Magical World of Disney Elder Davy Crockett Episode: “Rainbow in the Thunder”

1993–1997 Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman Kid Cole 4 episodes

1996 Renegade Henry Travis Episode: “The Road Not Taken”

1997 The Simpsons Space Coyote Episode: “El Viaje Misterioso de Nuestro Jomer (The Mysterious Voyage of Homer)”; voice acting role

1998 All My Friends Are Cowboys Himself Television special

2014 Johnny Cash: The Man, His World, His Music Himself Television film; BBC Bio Documentary by Robert Elfstrom;[183] archive footage

Published works

Man in Black: His Own Story in His Own Words, Zondervan, 1975; ISBN 99924-31-58-X

Man in White, a novel about the Apostle Paul, HarperCollins, 1986; ISBN 0-06-250132-1

Cash: The Autobiography, with Patrick Carr, HarperCollins, 1997; ISBN 978-0-06-101357-7[184]

Johnny Cash Reads the New Testament, Thomas Nelson, 2011; ISBN 978-1-4185-4883-4[185]

Recollections by Johnny Cash, edited by daughter Tara, 2014; ISBN 978-0-930677-03-9

The Man Who Carried Cash: Saul Holiff, Johnny Cash, and the Making of an American Icon by Julie Chadwick, Dundurn Press, 2017; ISBN 978-1-459737-23-5

Cash, Johnny; Mark Stielper; John Carter Cash (November 14, 2023). Johnny Cash: The Life in Lyrics. New York: Voracious; Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 9780316503105. OCLC 1407575187.